I break my pandemic silence to comment on what seems to be The Big News which is all over the place. Oberwolf & the current owners of Linden Lab must have been able to pull some strings at the Wall Street Journal and got an excellent article on Philip Rosedale re-joining Linden Lab. But the truth is that the press release sent out by Linden Lab spread like wildfire — unlike anything we have seen in the media (conventional and online) since the Golden Age of 2006/7.

Personally, I see this incredible news as another move in a huge-stakes poker game:

The winner will be who bluffs the best.

The Contenders

Microsoft is Microsoft. They own Minecraft. ‘Nuff said. Or perhaps a few more things can be added: they have a huge cloud infrastructure and a developer-friendly, up-to-date-with-reality CEO/Chairman at the helm. Nadella turned Microsoft cool again — to the point of launching their own Linux distro (and guess what — people use it — even die-hard Windows lovers). And, of course, they’re a trillion-dollar business, with a foot planted firmly in the corporate world as well as on the commodity market. They know all there is to know about 3D environments and sell them routinely on the Xbox platform. And they even have a grab of the social media environment — they own LinkedIn, after all.

Meta is also a trillion-dollar business — with billions of users, not millions. They know how to squeeze their users dry for their profiling data. When their ‘mainstream’ platform — Facebook — starts to weaken in the public eye, they grab their competitors, buying them out and closing them, or absorbing their products and making them their own. They certainly understand what makes people tick and get drawn to social environments — where no mistakes are allowed — and know how to extend their all-encompassing ecosystem to all possible niche markets. And, of course, aggressively sell ads for all that.

However, they’re completely clueless about 3D platforms. Sure, they have a nice gadget — Oculus — but A Gadget A Metaverse Makes Not. Microsoft has cooler gadgets and much more adequately priced — which became ubiquitous. Oculus VR products are made by geeks for geeks — gamer geeks. You can’t use them on the go in your mobile device of choice — unlike WhatsApp, Facebook or Instagram. There is simply no way such a product will attract ‘billions’ of users.

It’s also true that they know next-to-nothing about 3D technical and environmental issues. They grabbed some top Lindens back in the day they acquired Oculus, and I’m sure that Zuckerberg was told that, in a virtual environment, content is king — and high-quality content takes time to be developed. Ok, so they threw 10,000 people at the problem, and started hiring another 10,000 people. I suspect most of them will be marketeers and the rest are 3D designers. The truth is that Oculus was bought eight years ago, and they have little to show. If it weren’t for Zuckerberg’s long pockets, their Horizon project (or whatever it is called these days) would have shut down ages ago.

Apple, who also says that they’re into metaverse-y thingies to please their investors, is mostly bluff. Their advantage? They were the first trillion-dollar company ever; they know what they’re doing for decades (even if you hate Apple and their ultra-closed environment and freaky corporate culture, you will have to admit that their strategy worked, financially speaking; Apple shareowners are always happy with their returns, and, ultimately, that’s what matters for a business). But they have an ace up their sleeves: they are not newcomers to 3D environments. Aye, they had a 3D virtual environment before the turn of the millennium (and no, I’m not talking about QuickTime VR, which was a different project altogether). It’s not talked much about. It was an utter financial catastrophe, and, like the Newton PDA, Apple pushed that ‘mistake’ into oblivion. However, as we all know, a lot of the conceptual work done for the Newton was later re-branded as iOS (just as Jobs’ NEXTStep operating system became the core for Mac OS X, later macOS). So-called ‘abandoned’ projects — because they were not commercial successes — are often re-used by Apple years or decades later, when the time is right. Look at what they have done with Apple Silicon chips. Their origins predate even the PowerPC alliance that was so keen to compete with Intel; Apple already had chip-designing engineers in the early 1990s. And when Motorola was slipping on their PowerPC deliveries, it is now a well-known fact that if it weren’t for the teams of Apple engineers that were debugging the chips and showing to Motorola how they should have designed them in the first place. At the end of the ‘AIM’ alliance, it was Apple basically doing all the work. But… they lacked the money and resources to create their own chip factory, so they partnered with Intel for a generation. But now? They’re showing that their several-decades-old experience with chip design is paying off. It’s not unlikely that Apple can patch together something out of their ancient, abandoned 3D virtual world project, grab a company or two, and enter the arena fully prepared to be the market leader — that is, the company whose products others aim to emulate and beat. After all, that’s what Apple does.

Google, of all contenders, is possibly the one that has shown most promise, having launched technology after technology that could enable the Metaverse, but… always fell a bit short on delivery. From (allegedly) pouring billions in Google Glass, to the low-end-VR-for-the-masses-DIY Cardboard, Google’s track record is hardly stellar. They certainly have done wonders with Google Earth, and the number-crunching they can do on satellite data in order to build 3D models from scratch, adding extra imaging from their Google Vans that produce those glorious experiences in Street View… Google has certainly harnessed a lot of technology to produce very advanced 3D visualisation technology. In other words, like the other contenders, they have the core 3D technology, and they have an assortment of VR displays in the market. They have also repeatedly proven that when you’ve got a top-notch developer team and vast masses of data to process (and the means of doing so!), magic happens. Where Google struggles is mostly in understanding how to build a social environment — especially one where people meet together, either by text chat, by voice, or even by video. In 16 years, they have launched 20+ different products to do that, all of which were eventually shut down — some in less than a year (such as Google Lively — remember how scared we were back then in 2008, fearing that Google would take over the metaverse in a few months?)

When the Metaverse isn’t

It’s worth remembering that ‘metaverse’ just happens to be a cool buzzword for something techie that, besides Neil Stephenson, perhaps only the Second Life/OpenSimulator community really understands. I mean, we have been on a metaverse for two decades. We know what that means. Or, perhaps more precisely, we residents have a good working knowledge of what makes a ‘metaverse’, and what doesn’t, and we even have the choice of two varieties: the centralised metaverse of Linden Lab, or the loosely-coupled, federated OpenSimulator. Both approaches, however, provide a very similar experience to the end user.

But ultimately what matters is that both have a valid business model, not merely some vague notes scribbled by overeager CEOs on an Excel spreadsheet, which are 99% wishful thinking based on ‘personal feelings‘ and not hands-on experience if that approach actually works.

In other words: the above review of the industry giants (and, who knows, Bezos may also be on the shortlist — I just failed to find anything metaverse-related being announced by Amazon) establishes their strengths and advantages in the field, but are these the only reasons for success? Take the earlier link regarding Google’s continuous failure at developing a stable chat application — ‘stable’ in the sense of being able to keep it around for more than a few months before shutting it down. What was the criteria they used to decide to close all those projects and move on? Number of users. Lively, according to some sources, managed to have up to 10,000 users logged in simultaneously: Google considered that this was way too low for their expectations as an ‘industry giant’, and, as a consequence, didn’t want to pour any more money into it.

Aye — but that was only after they had spent their money building that platform in the first place!

Google, of course, may argue that they can ‘afford’ to run some experiments, since almost all of their 20+ failed chat products were started by employees on their company-sponsored free time (around 20% of the time that each and every employee is allowed to use Google’s resources to develop their own ideas and projects, in the hope that some of those ideas actually develop into products), so the actual costs of running Lively were low, and they just had much higher expectations on the product once it attracted customers. It’s not clear to me — and I suspect that it wasn’t clear for Google, either — how exactly they intended to turn ‘customers’ into ‘profits’. Indeed, it’s ironical that the Web world is excessively worried with things such as ‘customer acquisition costs’, ‘click conversion rates’, and similar buzzwords that were invented to create metrics with which to analyse the performance of a web-based product, and establish the expectable profit out of such metrics. More users means more infrastructure costs, but the expense curve is not linear: cost-per-user is much higher at the beginning, when there are very few users, while the larger the user base is, the easier it is to get economies of scale. And that’s where all the profit will come from.

Independent OpenSimulator grid providers know very well what that means, and have felt it in their wallets. If your grid grows above a certain number of users, it becomes profitable; if something happens and a significant amount of residents move out, then you’re stuck with lots of expensive hardware and employee salaries to pay, and too much resources spread out among a handful of users — not profitable. Second Life also needed a reasonably large number of monthly users in order to stay afloat; it wasn’t profitable since day one, but, at some point, as long as the number of residents is kept above a certain upper limit, the economies of scale start doing their magic, and Linden Lab remains a profitable operation ever since.

Actually, there is not so much ‘magic’ as that. This is microeconomics 101, described by good old Adam Smith. After a few months of running your business you can just do some math and see when (or even if!) you reach the point where you can grow the number of users and the income they generate faster than the growth of your running costs to sustain that number of users. Simple math indeed, but it seems that the industry giants ignore it completely.

Facebook and Google, in particular, are really bad at that. They are still stuck in the pre-2003-dot-com-bubble concept that the only metric they need is the number of users. Given enough users — millions, if not billions — one will eventually be able to squeeze enough money out of them to have a successful business model.

Well, no. That’s not how it works. And we have almost three decades of Internet businesses showing exactly why this line of reasoning fails — and a bubble to demonstrate it. It’s not hard to predict when a business will fail, despite their number of users. We know how to calculate that. The problem is that all these CEOs have been spoilt by their success and stubbornly believe themselves to be above the common rules of economics — they believe themselves to be superior to Adam Smith (and his followers, of course) and that they’re able to ‘rewrite’ the history of economics by replacing it by a new model. One model, that is, based on wishful thinking that more users means more money.

Anyway… put into context, the question is how these companies wish to make money out of their hypothetical user base — especially when these users expect the Metaverse to be pretty much like a 3D version of the Internet, where tons of services and content are essentially offered for free.

This age-old dilemma has also a centuries-old answer: sell ads. And when ads are not enough to provide revenue, well, then sell profiling data. This became a huge source of income in the 21st century, and the likes of Google and Facebook rely on it for their core business. These two companies are also famous in having the idea that they built a hammer that will hit on all sorts of nails, and that all potential problems can be coerced to become nail-shaped, so that the hammer will always work. If it doesn’t, well, the problem is not the hammer, it’s the nails that refuse to be coerced into the correct shape.

Apple and Microsoft, on the other hand, have at least an inkling of what it means to use screwdrivers, because not all problems are nail-shaped. In other words, they are at least aware that there might be different ways of generating income from a large user base while still gaining economies of scale to deliver good quality service to those increasing number of users.

And that’s why previous attempts at using and abusing the words virtual reality have encompassed a whole range of products that had little or nothing to do with metaverse-y things. Quicktime VR wasn’t ‘VR’ at all — it was just an ingenious way of getting affordable 360º panorama photos into a display format that could be deployed anywhere. Nowadays, panorama photos are just a minor enhancement on all cellular phones and have become ubiquitous. Even the Second Life Viewer allows one to take such pictures!

Indeed, the closest attempt at something that looks similar to a ‘metaverse’ has been 3D games. Those follow well-known rules of economics. You can buy a license to a game which gets you delivered in a physical container — an easy model to explain. You can access a subscription-based game, where you pay a monthly fee. Or you can play free games that are ad-sponsored. In recent times (and perhaps not surprisingly at the same time that Linden Lab became profitable with Second Life…), game developers added a new source of income to their platforms: the ability to buy digital items that give users special powers to advance further along the game narrative.

While all the above are good reasons for the game business to thrive on the revenue companies are able to extract from their user base, the Metaverse — at least what we think that the Metaverse should be — doesn’t work under the same assumptions.

The Laws of the Metaverse

Therefore, Philip Rosedale is strategically positioned to deliver his warning:

Big Tech giving away VR headsets and building a metaverse on their ad-driven, behavior-modification platforms isn’t going to create a magical, single digital utopia for everyone.

Philip Rosedale, Linden Lab Press Release 2022-01-13

Philip is not being arrogant and aloof on this quote (although you might be interested in reading a deeper analysis of their press release). He’s bringing his personal experience over two decades to the stage. Linden Lab didn’t start as a software company: they started building VR headsets and other VR-related hardware first. It was only when they realised they needed to test those devices, and couldn’t find anything appropriate, that they came up with the idea of designing Second Life. At some point they figured out that people were willing to pay for joining their virtual world, while their hardware side of the business wasn’t going everywhere. So — they dropped it. Instead, they focused on figuring out a way to make money out of the virtual world platform

The First Law of the Metaverse: Find out where the money will come from. Hint: it’s not going to come from hardware.

Granted, it’s not enough to create a business model out of thin air and expect it to thrive. There are a few lessons to be learned along the way: when doing something new, old business models may not work, and new ones need to be developed (or old ones created from scratch).

Ask yourselves the following question: before Google started selling ads, what was their source of income?

In the tech world, especially the tech world still stuck to the pre-dot-com-bubble days, there is this naïve belief that you just need to deploy an amazing technology, and people will flock to it. Have enough people, and somehow a business model will emerge that will sustain operations. Although that model has been totally debunked during the dot-com crisis, it still fuels much of the imagination of prospective entrepreneurs. Somehow, they think, the difficult part is attracting users; but once they start using your service or product, eventually there will be a way to make money out of it.

Consider Exhibit B: Facebook.

Facebook is a post-bubble company. The question ‘what did Facebook do before starting to sell ads?’ is easier to answer: they did nothing. Zuckerberg had a moderate success, pushed MySpace and Multiply and so many other large-scale, generic social media platforms out of the market, but was stuck with a dilemma: how does he get Facebook users to pay for the costs of maintaining staff and infrastructure?

For years, therefore, Facebook’s answer was just to get more investment money to burn. To show the amount of ‘success’ they had, the only metrics they could show was user growth and user engagement: aye, Facebook did indeed attract far more people than their former competitors, and these new users did interact a lot more than they did on previous platforms. But what Zuckerberg couldn’t tell his investors was how he was getting money out of them.

By an ironic twist of fate, Zuckerberg turned to Microsoft to get help to deal with his troubles. He couldn’t ask Google, because Google was claiming to enter the social networking market (eventually buying YouTube) — and by then Zuckerberg could not be sure that Google would fail on all those attempts (except, well, for YouTube, which already had a successful business model that Google only needed to incorporate in their own ad revenue generation platform). So Microsoft sounded like the best partner in those circumstances.

And it worked. Microsoft — who runs the Bing search engine, and back in the mid-2000s still believed that they could compete with Google on that business area — already had a competing service to Google Ads. One that worked, and worked well, and generated plenty of revenue. All it required was users; the whole software was already in place. So, Zuckerberg closed a deal where Microsoft would provide the ads, Facebook would grow the user base, and they would split the profits.

Allegedly, they made one billion dollars on the first year that Microsoft’s ad platform was used.

Now, that was huge. From a sheer economic perspective, it’s far more important to have a platform that can generate a billion dollars per year than a platform that is able to acquire one billion users. Getting a billion non-paying users is a great achievement, sure, but a billion non-paying users are just costs of operation. Huge costs, in fact. Whereas having a billion dollars sitting in the bank by just selling a handful of ads — well, that is a successful business model.

I can’t quote precise dates, but naturally enough, Zuckerberg and his patient investors were delighted at the magic of selling ads. Finally, they had found their successful business model. Allegedly, Microsoft will also have explained how profiling worked, and how it contributed to more ad revenue, when the platform starts placing the ‘best’ ads for each individual user. Granted, Microsoft’s technology back then was probably not so advanced as Google, but that’s irrelevant: they had the technology. It worked — it generated huge revenues. It could always be improved later: money, after all, generated more money, and both Microsoft and Facebook could always hire more employees and tweak their profiling business.

Indeed, this went on for a few years (I believe that only two or three), until Zuckerberg (and his investors) got greedy. Why let Microsoft keep a share of his business, when all they did was to develop a software platform to deploy ads using profiling techniques? I mean, that wasn’t exactly rocket science, was it? (Well, yes and no, it’s definitely harder than it seems, but it’s a well-researched area of computer science, and, most importantly, Zuckerberg believed that it was achievable with his own teams.)

At the first opportunity, they didn’t renew their contract with Microsoft, and both companies went separate ways, with Zuckerberg placing all the knowledge he got from Microsoft’s tools and successfully replicating them and improving them with tools developed in-house. Microsoft was left to acquire LinkedIn later.

Zuckerberg — as well as millions of entrepreneurs out there — have been so successful selling ads and profiling data that this tool became their hammer: all that is needed to succeed in the world of amazing Internet technologies is to acquire a vast amount of users and sell them ads. After all, industry giant Google practically gets all their revenue that way. The history of failures of Google shows how little Google actually understands anything else but profiling their users and selling them ads.

Nevertheless, they certainly are experts at doing exactly that, and, so long as the ad-based and profile-based business model generates profits, they will continue to re-use that hammer over and over again.

There are certainly alternative concepts to fund an Internet-based business operation. And we can go back to Philip Rosedale again. When revenues from land fees started to weaken — the trend wasn’t exponential any more — Linden Lab turned to charging fees on the LindeX. The amount of transactions, after all, was increasing faster than the user base, and definitely much faster than what those users were willing to spend on monthly fees. There was a real incentive to shift to a slightly different business model. At the end of the day, Linden Lab’s success story deviates dramatically from what the industry believes to be the ‘only’ way of making money: monthly subscriptions or selling ads/profiling data. There is no third way.

Philip Rosedale, while still at Linden Lab, proved otherwise: there are other ways which are adequate for the ‘upcoming’ Metaverse. But they defy mainstream Internet business. They require thinking outside the box. And, to be frank, they might not become mainstream: the learning curve to enter the currently existing Metaverse is incredibly steep, and that inevitably leads to a marginal growth of the existing user base.

But aren’t there other alternatives of making money out of the Metaverse? One that allows sustained growth in the user base, without requiring a steep learning curve to join?

Welllll…

The Second Law of the Metaverse proclaims that, in truth, there is no field-proven way of making money out of the Metaverse (enough to cover its running costs and make a profit!), besides the one introduced by Second Life (and OpenSimulator, of course, which replicated the same model at a different scale).

I’m obviously not so arrogant as to claim that ‘only Philip can get it right’ (more precisely: only Linden Lab know what they’re doing) — especially because, as we all know, Second Life started (in the alpha) without any inworld money and no permissions system: everybody owned everything collectively. According to legend, it was Lawrence Lessig who sort of persuaded some key figures at Linden Lab that they ought to create a virtual environment where ownership of digital content — as well as ‘creative commons’-like permissions — should be a possibility. If this is more myth than reality, I have no idea (then again, both parties never really retracted that story), but it’s true that Linden Lab, just as so many other Californian companies, also started with no clue about how to actually make money from the virtual environment they’ve built. To their credit, they at least expected to use a subscriber-based model (what we still have in the form of Premium residents). That went down the drain, but at least it afforded Linden Lab the opportunity to test around with other business models, and eventually figured out one way of making enough revenue to pay back their investors, hire more staff, and still make a decent profit.

Also, I’m not saying that there is no other way. I’m just pointing out that this is not the route that any of the other Metaverse-wannabes has attempted. Each and every one of them just assumed that all they need to have is a lot of users and cool tech — the business part of it would take care of itself somehow. Kudos to Philip on High Fidelity for at least exploring the idea of using concepts similar to how cryptocurrency works to fuel their attempt at a virtual world, namely, the idea of tying CPU power to payments — use someone else’s computer to host content, and you pay them for their troubles; and, vice-versa, allow people to store content on your computer and you will get paid for it. This is not quite the principle of how ‘mining’ cryptocurrencies work (you essentially get paid for consuming CPU & electric power to write an entry on the blockchain ledger), but there were some inspirations there.

Sadly, it didn’t work out as Philip intended. But I’d say he was the only one who was at least attempting a different business model. The rest of the crowd doesn’t. They all expect money to flow from ‘something else tied to having lots of users in a cool, techy environment’. That means ads and profiling data, or, if it doesn’t, nobody has been clear enough about the details.

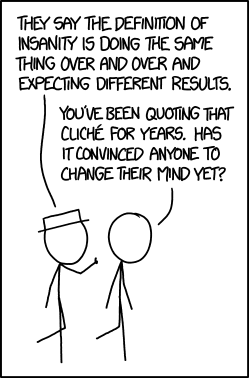

As we’ve all heard:

The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

Wrongly attributed to Albert Einstein

On the other hand, we cannot escape xkcd‘s irrefutable logic:

That said, I’d most certainly place my bet on Linden Lab, and wish Philip Rosedale a happy return to the helm.

Eventually, all the competition may start wondering what they have been doing wrong for the past two decades or so, and why Second Life has survived for so long — and why the only ones replicating Linden Lab’s business model (the OpenSimulator grids) also thrive on the same business model. There are a few variations among grid operators (Kitely having the most innovations), but, conceptually, all of them are using the very same business model as Linden Lab and getting enough revenue to stay around for years (not months), without the need of burning venture capital constantly (or whatever funds the likes of Microsoft, Facebook, Apple et al. have poured into their own metaverses).

The receipt to success is all there in front of anyone who cares to do some market research.

I will watch with interest if anyone among the Metaverse-wannabes will be among those, but my guess is that no one will, and, as a consequence, the infallible logic of the ‘insanity’ quote will descend upon all those projects, terminating them with utter prejudice.

In fact, half of my blog entries — if not more — have, at one time or the other, prophesised the end of [insert name of Metaverse-wannabe here]. Again, just using the ‘insanity’ quote, it’s really not very hard to make such predictions: they’re little more than self-fulfilling prophecies. They can just take more or less time to fulfill themselves, depending on how much money the company is willing to burn into their attempts. The current set of contenders have a lot of money, and they can maintain a project afloat for years if not longer, so long as they can persuade their stakeholders to allow them to throw money out of the window. They can afford that easily enough; they all have more than enough spare cash around for that.

Ultimately, the question is not really if those Metaverse-wannabes will succeed, in the business sense of the word. It’s rather that Linden Lab may start to feel the pressure of the market — a market with players orders of magnitude stronger (read: wealthier) than them. They can afford to lose money for years or decades, just to make sure there are no competitors left. Linden Lab, by contrast, has to be profitable every year, lest they start defaulting on employee payments. Linden Lab is owned by respected, reputable, bona fide investors that are in the serious business of making money, and, so long as Linden Lab makes money, they’ll be happy.

But how, you do ask, could Facebook Horizon (to take an example) push Linden Lab out of business, if Horizon has little in common with Second Life’s conception of a ‘metaverse’, and nothing in common with Linden Lab’s business model? Surely, Second Life can always compete in a niche market that nobody else understands?

Well, there is a small, non-negligible risk from lobbying.

You see, all those industry giants are wealthy enough to cheat. If they figure out that they cannot get their own version of the metaverse to thrive (and become profitable at some point), they can eventually push governments to change the rules, so that Second Life is excluded from the market. Suppose, for instance, that Facebook is able to force Tilia to shut down by lobbying a few representatives to pass a law that removes Tilia’s accreditation as a payment gateway. This is not too far-fetched — just remember how the roles were reversed during the days of wildly unregulated Linden Dollar currency exchanges, banking, and other financial products. During those days, in order to ‘protect’ their customers, they had no other choice but to declare non-LindeX currency exchanges illegal and force them all to shut down their business, one by one. I’m not going to argue for or against that decision, but it was no coincidence that it was made in the middle of massive international law changes to get online business transactions better regulated; a lot of players dropped out of the market, not just the tiny organisations sprouting around Second Life (anyone still remembers eGold?). Linden Lab, as the entity ‘coining’ Linden Dollars, could get in trouble because of that, and they needed to safeguard themselves against the much stricter regulations that started to appear all around the world.

It is not too far-fetched that Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, Google, etc. could push for even stricter regulation. All of them have their own payment services or gateways, and they frown upon the competition — especially the competition from the tiny fish in the pond, such as Tilia. Tilia might be forced to operate under such rigid conditions that it would have no choice but to shut down their operations — because there is a limit to how much they can bear the cost of implementing such regulations — and that would threaten the whole business model around Second Life. It’s not as if there aren’t alternatives around there (after all, Second Life could continue to thrive by using the payment gateways of those industry giants instead of their own…), but there is also a question of margins. Being forced to accept another intermediary would mean shorter margins — and these would also be reflected in how much you would need to pay to exchange L$ for fiat currency. There is a limit to how high Linden Lab can go before people start to drop out of Second Life (especially those that are big movers of L$/US$ transactions); and there is a lower limit that Linden Lab can set before the whole operation is simply not profitable any longer…

This, naturally enough, is just one possibility. Forcing Linden Lab to remove all adult content, for instance, would be another one. There is really no limit in the ability of lawyers and lobbyists to come up with arbitrary rules to interfere with what currently is a reasonably free market. If that happens, Linden Lab may be in for a rough ride, as they navigate across legislation in order to stay afloat.

Nothing of the above has anything to do with how Linden Lab operates Second Life as a business. That model has proven, over and over again, that it works. But it only works assuming that all the players in the market are fair. When they start to cheat, the market is not ‘free’ any longer, and even the soundest business model can be forced to shut down.

That’s possibly one of the many reasons why Philip Rosedale is back on the helm. Not just because he is our hero figure, and not because he’s not afraid of ‘going against the giants’. These are certainly very good reasons (and there are many more!). But I also think that one of the roles that Philip will have to play — and play well — is the role of the ‘guardian of the free market metaverse’. He has the charisma for that, and a good foothold on the history of the Internet, too (if it weren’t for Philip, we might still not have podcasts these days), enough to attract the attention of some journalists, if the giants start to play unfairly.

Philip’s role, therefore, will also encompass defending the freedom of creating (and running) a Metaverse, and prevent it to become a regulated oligopoly with just a handful of players. The ‘David against Goliath’ theme has proven to be popular with the conventional media, over and over again. Philip will need to push Linden Lab back in the limelight as soon as the giants start misbehaving — which they will. It’s not just clear how and when that will happen.

Therefore, for the time being, Philip has had no qualms telling publicly that you cannot make a metaverse to work solely based on ads and profiling data. Because his business model is transparent, well-known (if perhaps understudied by academia), and showed results for almost two decades, he can easily take the role of ‘going the high road’ and set the example that others must follow. Granted, we all know how bad Linden Lab’s own PR has been. But I’d say that the latest press release, announcing the Return of the Linden Jedi, was very well received — on the same day, dozens or even hundreds of conventional media outlets republished it, and I guess that Waterfield & Oberwager had a hand in it.

So, that’s what we know how Linden Lab will enter the poker game. They have some good cards, and the ability to bluff their way ahead. Even if their bluff is called — Second Life, after all, is just a few-million-dollar operation, not a billion-dollar business — they can at least remain long enough at the poker table to cast some doubts on the other players.

I would definitely say that the best bluffer will win — but Philip Rosedale will at least try that they all play fairly, according to the established rules, and try not to cheat by changing the rules.

It should be an interesting poker game to watch.

My thanks to the vast quantity of authors posting their articles on this subject all around the whole SLogosphere, which kept me amused and entertained for quite a while, persuading me to dare to post something on my own, after so many months (years?) of silence!

And my heartful wishes of success to Philip, of course.