What does that mean, “be a niche product”? It’s not like it’s a bad thing. Just take a look at another niche product: Adobe Photoshop. It’s a rather expensive product. It’s designed for specialists who require the whole set of features it has. Regular, mainstream users don’t really need to use Photoshop, there are tons of cheaper and simpler alternatives. Nevertheless, this never stopped Adobe from making millions. In fact, you can take a look at all the specialised applications out there, designed with niche markets in mind, and see how immensely successful they usually are. Think about Autodesk (AutoCAD, Maya, 3DS); or about software for DJs, for movie producers, and so forth. All these have “hundreds of thousands” of users — sometimes “a few millions” — and never complain because they’re not “mainstream” products like, say, Microsoft Office.

There is this huge fallacy that every product or application launched has to be mainstream or be doomed to failure. This is hardly the case for tons of products out there. Even, in a sense, some “mainstream” products can be targeted to niche markets as well. Think about luxury cars, for example. Or Apple, the world’s most valuable company. You can even think of extreme examples like companies manufacturing satellites, or components for oil platforms. None of these are mainstream products but highly specialised applications for a relatively small market. And many are among the most successful companies in the world; they don’t need to be Proctor & Gamble with their mainstream products to be rich!

What is so different about companies specialising in niche markets? Well, first of all, they are in constant touch with their customers. Since they recognise from the start that their clients have special needs — because they’re in a very small market! — they need to know exactly what they want and deliver that — not more and not less. Unlike mainstream products, which have to deliver one-size-fits-all products which make the most amount of people happy, niche products need just to address specific market needs, but do them very well. Good examples are how niche markets become “brand cults”; examples are Harley Davidson or BMW, and most certainly Apple as well, but there are thousands more. Outsiders — “mainstreamers” — cannot even understand the appeal of the product or why it is so successful among the community of its users. More to the point, they might not even understand why a BMW fan will pay premium for a BMW bike, when a common Yamaha or Honda also has two wheels and a motor 🙂

Niche markets saturate quickly; they expand, if at all, very very slowly. That’s just because the number of people willing to be consumers in that market is always small. Sometimes, it’s just because they require special skills — Photoshop, for example, appeals to graphical designers, but it requires a lot of talent and skill to put Photoshop to good use. If you don’t have either, but still need to do some photo editing, you don’t need anything as complex as Photoshop. Similarly, if you’re not an architect but want to jot together the plan of your future home to discuss with an estate agent, you don’t need to learn how to use AutoCAD; SketchUp will do the job much easier — and much cheaper too. The number of people that actually need to use the product is not big, and, more to the point, doesn’t grow that much. Eventually there might be some sudden growth because of some sudden, unexpected, market change. Take a look at Photoshop again. It existed well before the Web was popular. But suddenly the Web was “invented”, and graphical designers now needed a tool that also allowed them to create Web designs. Photoshop was a natural choice for them — it was something they were already familiar with. So Adobe launched new functionality to make Photoshop more appealing to graphical designers who also did Web pages. But by chance they also got a completely new market, of aspiring web designers, which didn’t exist before, and started shopping for tools to help them do their job better and faster. Similar “sudden growth scenarios” happen often, when there is a market change, and a company suddenly retools their product to address that quickly, and reaping the rewards until the market saturates again (I guess that web designers are not “mainstream users” but their number grows so quickly that the exponential growth hasn’t stopped yet…).

But usually that’s not how niche market companies exploit their market. What they do is upselling. In the software world, this used to mean licenses: release a new version with new features and get all your existing users to pay extra for a tool they already owned. The big software industry names addressing niche markets still use that model. Others are a bit more clever: they just launch more and more tools, that work with the original product but extend its functionality. This is a bit more honest — clients pay just for the features they need, not to constantly upgrade what they already have — but both models are frequent (just try to look at Adobe’s product line with its complexity of different packaging the same set of tools together in completely different ways to see what I mean!).

Upselling is always easier than getting new customers. To draw more new customers, you need a marketing strategy that reaches out, does advertising, finds where the potential consumers are, do market analysis, and so forth. It’s costly. It pays off if the market is big enough. But on small markets this might be pointless to do. Just ask your existing customer base what kind of tools they cannot live without and tag a price to them. Keep in touch with them — after all, you already have their addresses! — and invite them to participate in testing, discussing, and collaborating in new releases. Adobe was very clever with the Photoshop plugins — I’m not sure if they have been the first to develop that concept or not — and even cleverer by providing a marketplace for them as well.

This is also a side-effect that is common on niche markets: the companies tend to encourage their customers to participate in the niche economy as well. Everybody benefits! The company will be seen as “friendly” because they support their customers by helping them to sell their own work; and customers remain loyal because they know they can also make a bit of extra money if they continue to work closely with the community around the company. Just to give you a different example, take a look at Myriad Software. They’re a tiny French software house which has been around for a decade or so, and which has close ties with universities. They develop something very specific: a software to compose music, for professional and amateur composers. This is not something easy to use like, say, Apple’s GarageBand. But it’s something where you can orchestrate a symphonic piece in the traditional way, and play it on your computer. The number of composers world-wide is tiny, but still, there are quite a lot of software that accomplishes the same thing (Sibelius being probably the market leader). So to effectively compete, Myriad Software developed a community of composers, by encouraging them to contribute music and arranging some contests. Many participants are actually composing students which join the community and submit university assignments 🙂 The software is also extensible. New features are implemented thanks to a feature voting tool. Now these guys are not “industry giants”, and they know that they cannot compete with massive advertising on specialised magazines. So instead they focus on the community and keep closely in touch with them. And they try to help any community projects as much as they can: for instance, if you decide to ask them to sponsor a composition contest, they will gladly give some free licenses, so long as they can post some articles about it and make an announcement on the forums and newsletters as sponsors — which in turn will spread the news to potential contestants.

Obviously there are many, many similar examples. BMW also holds meetings together with bikers and let them participate in some design projects. They sponsor community events and have a marketplace for used bikes and spare parts. At the same time, they also license the brand for inclusion in merchandising. And occasionally they sponsor community events and send a few representatives there — speakers, evangelists, even some managers. All are seasoned bikers as well, so that the community is comfortable in having the “suits” around.

I suppose you’re seeing a pattern here. By focusing on a niche market, perfectly understanding that the product will never reach the mainstream, a company can completely change their strategy to be fully committed to the existing community instead of “dreaming” about a potential mainstream market that doesn’t exist. That commitment has lots of aspects, but it means mostly listening to what existing users want and develop just that. It means enabling current customers to somehow make some money out of the community, and sponsor that endeavour. And, of course, it means releasing new tools, upgrades, kits, or whatever is appropriate for the kind of company, to upsell to the existing customer base. Sometimes they get lucky — like Adobe did, thanks to the Web — and the market can suddenly increase dramatically for a few months or years, and they can seize the opportunity. But most of the time the market remains at a small size and grows very slowly.

Adobe, AutoDesk, Apple, BMW — all are successful companies addressing niche markets, but so is the tiny, unheard-of Myriad Software. All follow some variations of that rule. Sometimes they are lucky, like Adobe was — and sometimes they have the touch of a genius like Apple with the iPhone, which pretty much turned an Apple product truly into a mainstream product.

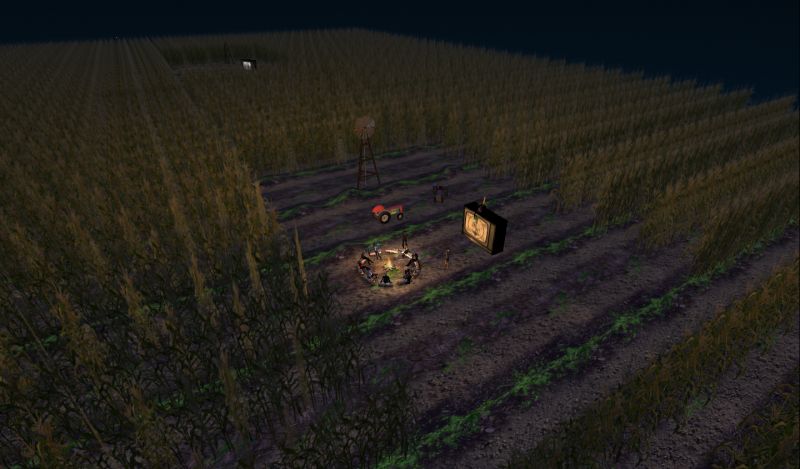

Now let’s switch our focus back to Second Life and its relation with Linden Lab. They’re actually not too bad: Second Life is mostly a community tool (so, unlike other companies, LL doesn’t need to create a new tool just to get the community together) and it already has a built-in economy. Clients — residents — make money out of LL’s product, and, in return, buy products and services from LL. LL has more than one way of allowing that to happen: land resale, LindeX, and the SL Marketplace are some good examples. So we residents are not “merely customers” but we also become participants in the overall economy, of which Linden Lab gets a slice. In fact, LL gets the smaller slice (according to their own numbers, at least), because, except for the SL Marketplace, they don’t charge anything for a L$ transaction. They are also doing something for the community, and Rod’s recent announcements show that they are possibly going back to the “old days” where Lindens and willing residents worked closely together to create a better (virtual) world. This is an important step, but one that is shared by many mainstream companies as well.